Caxambú, Minas Gerais, Brazil. With the aid of a CLAIS travel grant, I spent part of the summer of 2018 in southeastern Brazil conducting my master’s thesis research on a local new religious movement. Studying this contemporary religious phenomenon requires an understanding of the socioreligious background and the local environment against which it emerged. I took this photo when I stopped by Our Lady of Remedies church (Paróquia Nossa Senhora dos Remédios) in Caxambú, Minas Gerais, a town in a region that became known for its healing waters and deep faith. The church stands adjacent to the central water park where, in 1868, Princess Isabel of Portugal famously drank of the healing waters and became pregnant soon thereafter. This photo of the main church, still bedecked in the July festival (festa junina) flags, represents this embodied spirituality, the human wholeness that can come from an enacted faith performed in connection to the land.

Soledade de Minas, Minas Gerais, Brazil. With the aid of a CLAIS travel grant, I spent part of the summer of 2018 in southeastern Brazil conducting my master’s thesis research on a local new religious movement. Studying this contemporary religious phenomenon requires understanding the local environment in which it emerged. The members of this new religious movement stress the importance of being close to nature when undergoing the movement’s 21-day fasting initiation. This proximity to nature helps anchor the practitioner in the present moment, the moment in which the human ego is obliterated and our true, Divine nature emerges. Many report feeling a kind of unity consciousness, a state of being one with all beings in the universe, which leads to an ethic of compassionate care for all life once the initiation has ended. This sunset landscape gives the viewer a little sense of the glory perceived by these initiates, an everyday miracle that requires engaged presence in order to be seen and appreciated.

This image captures the last moments of twilight, shortly after I watched the sun setting on the deforested landscapes of the Andean Foothills. Despite their beauty, these gorgeous rolling hills blanketed in clouds are regions that were cleared for livestock grazing. Many of the fragmented peaks that erupt from the cloud cover are effectively islands of rainforest –areas that have not yet been encroached on by agriculture. In a warming climate, these cloud forests will be even further at risk as the plants and animals endemic to their high slopes will need to retreat higher and higher to survive. This image was taken from near the peak of the Pichincha Volcano at around 4,000 meters, after an arduous hike to the top of the mountain. The view, and the landscape perspective it offered, was more than worth the climb. (Located an hour south of Quito, Ecuador)

Your Tropical Homestead Awaits *Plenitud Farm, Las Marias, Puerto Rico

Finca Paraiso *Plenitud Farm, Las Marias, Puerto Rico

Palm swamp during sunset in the Amazonian island of Marajó, Brazil.

Calm street in São Luís, Brazil, during the closing of Festa Junina, a popular festival in which Catholics and non-Catholics alike celebrate the nativity of St. John the Baptist.

The Palo Verde National park hosts the biggest wetland in Costa Rica. It is located in the lowland area of the Nicoya Peninsula, in the Guanacaste province, northwest of San Jose, Costa Rica. The wetland’s main affluent is the Tempisque River, which springs in the costarrican higlands, close to the border of Nicaragua. In the 1970’s, 19,804 hectares of what used to be pastureland for cattle were bought by the government to establish the National Park. Twenty years later, 50% of its surface are protected under the category defined by the Ramsar Convention of Wetlands. Its importance is paramount for wildlife species – such as caimans – and many migratory birds, - such as great Egrets and Roseate Spoonbills – who decide to reside in Palo Verde during the northern hempishere winter. All these species are vital for maintaining the healthiness of the ecosystem, as can be seen in the huge flock that adorns the blue skies. In March 2019, a group of students from the School of the Environment visited the Biological station in Palo Verde National Park. Despite its abnormal dry conditions, the wetland still holds a substantial amount of plant species, like the “Palo Verde” (in the Fabaceae-Cesalpinoideae family), which can be found all across the National Park.

The continental divide splits Costa almost in two parts: the Pacific side – known for its drier ecosystems – and the Atlantic side, known for the presence of lush wet tropical forests. Crossing the Costarrican highlands translates almost inevitably in a direct encounter with cloud forest landscapes. This fragile, yet quintessential ecosystem – both ecologically and for people’s livelihoods – has, for many years, been threatened by land conversion. Don Carlos inherited 120 hectares from his father, in what used to be almost barren land for cattle grazing. In the hills pictured above, Don Carlos, his daughter Ana and some friends started planting some trees and allowing the land to regenerate. Nowadays, these forests encircle the Cuerici biological station, which in the local indigenous language means “the place where the frog appears”. A group of Yale students from the School of the Environment spent 2 days identifying some of the many unique plant families that can be found in this place. In the background, the highest peak in the country - the Chirripo volcano, with an altitude of 3, 918 meters – blocks the moisture coming from the southeast, making this area extremely humid and rainy for most part of the year, therefore earning the name “cloud forest”.

Seeing a puma in the wild is rare, even if your life’s work is studying these magnificent predators. However, in San Guillermo National Park, where I am conducting my dissertation research on predator-prey interactions and nutrient cycling, puma sightings are relatively common due to the open habitat and extremely low human presence, which renders the animals more bold. My research team and I came across this puma during the course of our fieldwork, and after staring at us for a few moments it proceeded to mosey up to a tuco-tuco hole, catch one of the large burrowing rodents, and lie down and eat it in front of us.

Golden hour among the igneous intrusions of San Guillermo National Park, Argentina is always a magical time. Here, the vegetation grows thick because these volcanic rock forms provide excellent cover for pumas (also known as mountain lions), who frighten away the large herbivores who would normally graze down the grasses and shrubs in more open regions.

Two students observe the innovative agricultural practices at Finca Marta, an organic, sustainable agricultural project in Artemisa, Cuba, after receiving a tour from the farm’s founder. Finca Marta’s community-based agricultural model strives to remedy Cuba’s food shortage while preserving natural resources, engaging in ethical employment practices, and supporting local social service agencies.

A wrangler at a crocodile farm near Southern Cuba’s Cienaga de Zapata demonstrates the docility and friendliness of the baby alligator. The farm houses dozens of crocodiles and teaches tourists about the endangered Cuban crocodile, which now can only be found in the Zapata Swamp and the Isle of Youth.

Miramar, Cuba; Spring Break 2019 through Cuba Initiative

Havana at sunset; Spring Break 2019 - Cuba Initiative

“Cotopaxi Canoe” was taken directly within Volcán Cotopaxi in the province of Pinchincha, Ecuador. During the summer of 2018, I had the distinct opportunity to study abroad in Quito, Ecuador, through Yale Summer Session Abroad. While many lessons were taken away from this South American journey, one of the most important was that peace and adventure can be found in the same place. Just like this canoe, Ecuador is a peaceful place, filled with beautiful landscapes and warm-hearted people. But just like this volcano, Ecuador is filled with adventure and surprises. Finding peace on a canoe in the middle of a volcano was just the unexpected respite I needed after a long day of travel during one of the program’s weekend excursions. Finding peace in the midst of an Ecuadorian adventure was exactly what I needed to solidify my love for Latin America.

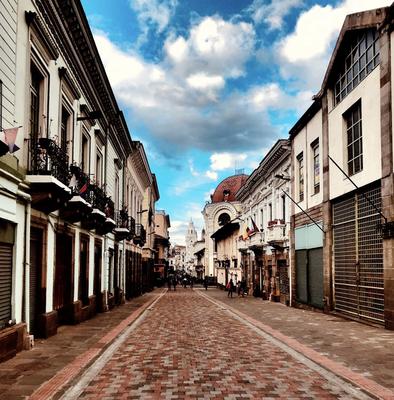

“Las Calles de Quito” was taken while visiting the Centro Histórico de Quito, Ecuador’s colonial center and one of the most important in Latin America. While many beautiful statues and buildings are situated within the center of the Centro Histórico, one commonly overlooked aspect of the Centro is the beauty of its everyday shops and houses. During the summer of 2018, I had the distinct opportunity to study abroad in Quito, Ecuador, through Yale Summer Session Abroad. Everywhere I turned in the country, I was amazed by the intricate architecture and use of space. These buildings, aligned perfectly to provide a dazzling vantage point down the slanted Ecuadorian streets, provide some insight into the simple beauties of everyday life in Latin America. These simple beauties made my Ecuadorian experience worthwhile.

Coyoacan market is a colorful and bustling market in Mexico city. Yet not everyone is privileged enough to have a stall inside it. Lots of street vendors flock the nearby streets. Here María sleeps soundly on the street while her mother sells traditional handcrafted textiles, waiting for the next tourist to stop.

This ceiba is the last and only remnant of the tropical rainforest, once widespread. Intense deforestation in southern Chiapas is decimating the last Mexican tropical forests. Yet ceibas are considered sacred trees and are not felled. This way they provide shade for cattle and avoid soil erosion.

Friends walk down a street in Havana, Cuba. The distinctive architecture and unique history was one of the things that drew me to Cuba, and one of the most fascinating aspects of my time there.

Valley of Viñales, Cuba

Two indigenous highland Peruvian women sit among the fruits of their labor on a congested camino peatonal in the historic highland silver mining capital of Cerro de Pasco, Central Peru. The vast mine at Cerro de Pasco once funneled silver to the Spanish crown and remains a billion dollar industry. Legends tell us that 400 years ago, the rocks surrounding Cerro de Pasco wept silver. Today, the people weep; their tears are thick with lead dust and other environmental contaminants. The area has been called Peru’s Chernobyl. Its red-cheeked children fall among the highest in global rankings of lead poisoning and the edges of the city have literally begun to slide into the pit. Its landscape is dusty, post-apocalyptic, and vaguely martian, ringed by mountains of gray pit mine sediments and dotted with waterholes turned neon orange by mining runoff. Below a smog-layered colorless sky and amidst the solemn bustle of a crowded central thoroughfare, two highland women sit surrounded by a kind of wealth born far away from this place. The cumulative effect of their offerings– mounded, abundant, bright, and imbued with vital force– injects a powerful sense of vitality into a city whose 400 year old open pit mine now literally consumes it. The women feed the people; in a cycle reminiscent of Taussig’s (1980) seminal work on the tin mine industry of Bolivia, the people then feed the earthly jaws of a kind of global economic beast– with their homes, their children, their lives. The cycle continues. People consuming, people consumed.

I visited the astonishing city of Cerro de Pasco in Summer 2018 while negotiating an archaeological project with regional governing officials. Archaeology may proclaim distance from modern geopolitical affairs, but it inevitably intersects with the lives of people today. This is especially true in the case of New World archaeology and its relations with indigenous peoples. This visit spawned a critical reflection of the parallels of two extractive industries, mining and archaeology, and the ways that both seek to downplay their effects on the lives of local populations.

Yale undergraduate students excavate the remains of 2500 year old residences at the mountaintop site of Chawin Punta, one of Central Peru’s oldest known and most remote highland temple complexes. One student explores a hearth feature while another prepares archaeomagnetic dating materials with a mortar and pestle.

The site represents some of the earliest evidence of the spread of the famous Chavín religious phenomenon in the Andes. The importance of the Chavín religion in Andean prehistory is difficult to overstate; it was a cultural and religious tradition that came to unify the Andes in a hitherto unprecedented way over the course of nearly a millennium. This history has become an important element of contemporary Peruvian national identity.

Further information about the photo: I took this photo during Summer 2018 excavations of the Chawin Punta archaeological project, directed by a friend and colleague who is a PhD student at Yale. I am a long term member of the project who has been working there as a methods specialist and will return this summer. Last year we excavated for several months and brought three Yale undergraduates for excavation training.

The winter of 2017-18, I spent 6 weeks in Mexico City doing research on the enforcement of human rights obligations in Latin America.

It was the first time I had been to Mexico City. I was traveling alone, and I was excited by the opportunity to engage with the city on my own terms. And most of the time, the vibrance of the city energized me. But at other times, navigating this city alone left me feeling like a rock suspended in time – motionless as the world whizzes by. This picture was taken at such a moment.

I was eating lunch by myself in an empty restaurant. It was an odd space without walls that normally would have shut out the busy street outside. The contrast between my solitary meal and the chaos surrounding me could not have been more obvious.

It was midway through that meal that I noticed my friend stop, detach itself from the activity outside, and sit down at the entrance. My moment of solitude was broken: there were now two rocks suspended in time.

This photo highlights Afro-Colombian entrepreneurs (who quickly became friends) at a flea market in Usaquén, a neighborhood in Bogotá, Colombia. Communing with them on Sundays, I learned from their life stories, their diverse backgrounds, their pasts and hopes for the future. Over hot chocolate from Chocó, the majority-black department on Colombia’s Pacific coast, they shared with me their perspectives on life for Afro-descendant people in Colombia, especially in the majority-white capital of Bogotá. At this sprawling market, popular among tourists and Colombians alike, they comprised a mere handful of venders of African descent. They introduced me to different foods, music, and dancehalls than those typically recommended to me in Bogotá. Meeting them while conducting dissertation research was extraordinarily impactful personally and professionally. I learned of their perspectives of my research on slavery in Colombia, and the work that this history contributes by informing their present political struggles. I sampled the delicious chocolate bars, and I finally learned how to tie a head wrap, which made me feel more connected to my own heritage despite our different nationalities. In our shared identity as children of the African Diaspora in the Americas, we established connections in our shared historical origins and our paralleled conditions in the present – the continued struggle for recognition, dignity, and equality. They reminded me of the urgency of historical scholarship in the present.

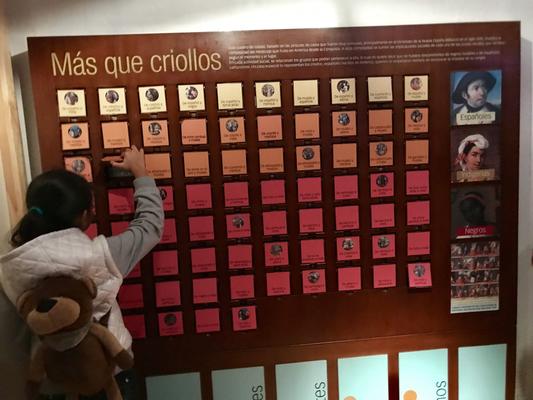

I took this photo in a museum in Bogotá, Colombia. It fascinated me to see attempts to integrate conversations about race, ethnicity, and African and indigenous heritage in educational sites intended to foment national identity. Here I was, a graduate student researching slavery in colonial Colombia, at times wondering if the painstaking work of archival research makes a difference today, when the urgency of the global Black Lives Matter movement echoes, and struggles for gender equity, political representation, and against health disparities loom so large. Turning the corner I found this grid system that outlined the sistema de castas, the racial caste system intended to classify people by their combinations of racial mixture under Spanish colonial rule. It clearly resonates today, though two things fascinated me: first, the phrase “Más que criollos” (“more than creoles”), which was a running theme in the museum. It emphasized that Colombian and Latin American history is not limited to the lifestories of creoles (people of Spanish and indigenous origins). It’s a phrase that stayed with me throughout the duration of my research trip. It’s one thing to know that history is more than what’s represented by the demographic majority, but it’s another thing to document and demonstrate through my research. Second, I was struck by how interactive this portray was, and that it was meant to be accessible to children, which reinforced the vitality of historical narratives for our aspirations of the future. I moved quickly to capture this young girl’s curiosity, while she interacted with a narrative of the past and likely reckoned with her place in it.

Pena Palace in Sintra, Portugal. March 14, 2019.

Mosteiro dos Jerónimos in Lisbon, Portugal. March 13, 2019.