Learning in Cuba

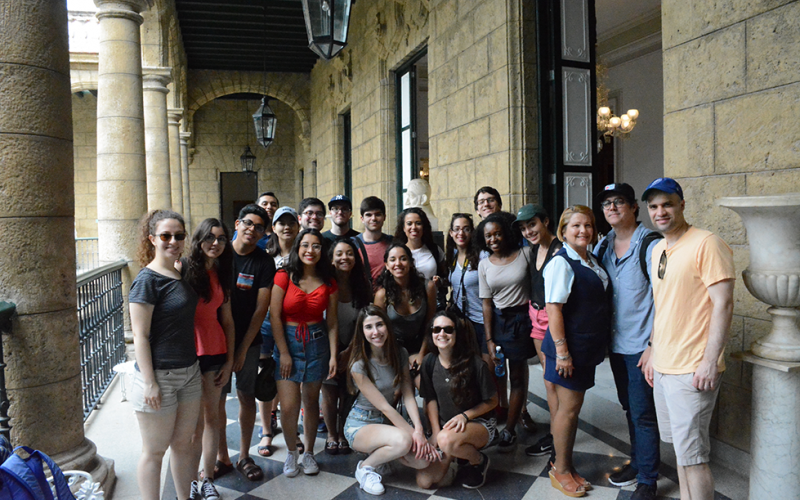

Maile Speakman, an American Studies doctoral student ’22, wrote the following article about her return to Cuba as the Teaching Fellow for the “History and Culture of Cuba” course a decade later. Maile, along with Professors Albert Sergio Laguna and Reinaldo Funes Monzote, accompanied 18 undergraduate students on the trip, which is the signature piece of the Cuba Initiative housed in the Council on Latin American & Iberian Studies at the MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies.

The course introduces students to Cuban social, political, economic, and cultural history from the colonial period the present. It focuses on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with special attention paid to the 1959 Cuban Revolution within the context of the Cold War. It examines the relationship between Cuban society and nature; the intersections of race with enslaved labor, art and Cuban national identity; the Cuban diaspora in the United States; accomplishments and critiques of the Cuban Revolution; and the long history of U.S.-Cuba relations. Students will engage with history, literature, film, music, television and other popular culture forms. The heart of the course is the class trip to Cuba during spring break, which is funded by the MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies.

In 2007, eager with excitement and anticipation, I boarded a plane in Cancún with 27 other Lewis & Clark College students who were en route to Havana. In those days, there were no direct commercial flights to Cuba from the United States. The airplane cabin was abuzz with chatter as we speculated about what our experience for the next four months would be like. In that moment, I found that I had many questions about Cuba. Some of my questions included:

- How does a communist country survive in a capitalist world? Why did Cuba remain communist while countries in the former Soviet Union transitioned to capitalism after 1989?

- In what ways has the Cuban Revolution addressed racial and gender inequality?

- What is the role of censorship in Cuban society?

- How does the U.S. embargo impact Cuba?

- How did 80 people on a boat seize control of the entire country in 1959?

- How do things like property distribution, labor, and consumption work outside of a capitalist model?

Over ten years later, while traveling in Cuba with students from Yale’s 2018 History and Culture of Cuba class, I heard many re-articulations of these questions along with questions I had never considered before. As the class teaching fellow, I was energized by the intellectual engagement and deep curiosity of each of my students. Through my attempts to answer each one of their questions as we visited Havana, Viñales, Varadero, Cienfuegos, and Trinidad, I grappled with Cuba’s immense complexity. Cuba is a place of many contradictions. It is a site where a long-standing Marxist revolutionary regime partners with multinational companies to create all-inclusive tourist resorts. It is a site where resources are incredibly scarce but homelessness is nearly non-existent. Cuba is the home of Che billboards, the Guantanamo Bay Naval base, two currencies, and a number of cultural practices (like baseball) that directly gesture to Cuba’s past ties to the United States.

Havana’s Vedado neighborhood, where the class stayed for most of our two-week stay, is a place that has been particularly marked by U.S. influence. In Vedado, U.S. modernist architecture and art deco buildings populate the urban landscape. Vedado is also a neighborhood where one can buy a hot dog, go to the movies, eat pizza, stroll along the malecón, take a collective taxi ride in a run-down 1950s Ford, eat ice cream, or hang out in the Habana Libre hotel (which was once the Hilton.) As the students explored Vedado, I wondered what felt familiar to them and what felt strange. I know the movies and ice cream are cheaper (less than 25 cents USD to have both!), the lines are longer, and that navigating a two-currency system was new for everyone. However, I’m curious if the urban landscape and all its signifiers of a past U.S. presence resonated with the students or even felt distantly familiar.

I likely wonder this because Vedado was what captivated me most when I studied in Cuba in 2007. As a site of leisure, consumption, and youth culture, all I wanted to do as an undergraduate was hang out in Vedado. Though I can’t relay each student’s experience of Cuba or even begin to fully document every learning experience we collectively had in Cuba, I can say that I think students truly learned the most during their free time in Havana. Free time in a new place is an opening for learning that cannot happen in the boundaries of a classroom in New Haven. Both as an undergraduate and now as a graduate teaching fellow, I relish in the time I have spent learning about Havana through the practice of “flânerie,” or aimless wandering. By strolling through the cityscape, buying palomitas from a Cuban retiree, and facing Florida while gazing out to sea on the malecón, one can learn a lot.