My Latin American Summer Experience: Chucho Martinez

This week, we are excited to launch a new series featuring stories written by students who received CLAIS´ support to conduct research in Latin America. This time, Chucho Martinez, B.A. Architecture, Pierson College ‘23, shares his life-changing experience in four South American capital cities this last summer.

His project title is:

(De)Humanizing Inhabitation: An Ethnographic-Architectural Exploration of 20th Century Latin American Mass Housing

For seven weeks this summer I traveled around Latin America with funding from the Steven Clark Senior Essay Travel Grant. While my original proposal was focused on functionalist mass housing projects and experimental housing, I soon realized that this scope was restrictive and that I would miss out on a comprehensive understanding of Latin American housing if I adhered to it. While initially proposing to visit twenty-one sites, I ended up visiting thirty-nine. Apart from the residents I talked to, I had the good fortune of meeting academics, architects, and government officials who took me around their cities and helped me uncover the nuances underlying the historical and current conditions of housing in urban Latin America.

In Bogotá, I visited one of the largest and most infamous

barrios—Ciudad Bolívar. A newly opened cableway crosses the immense expanse of self-built and codeless homes. A trip on the cableway takes thirteen minutes to arrive at the last station, replacing the former two-hour drive (Figure 1). The Transmicable culminates in Ciudad Paraíso, the youngest and most marginalized community of Ciudad Bolívar. This last station is adjacent to the

Museo de la ciudad autoconstruida, a museum-community center where the inhabitants seek to educate locals and visitors about the merits of self-building, as well as to commemorate the history of the migrant and indigenous communities that began to settle in this area since the 1950s.

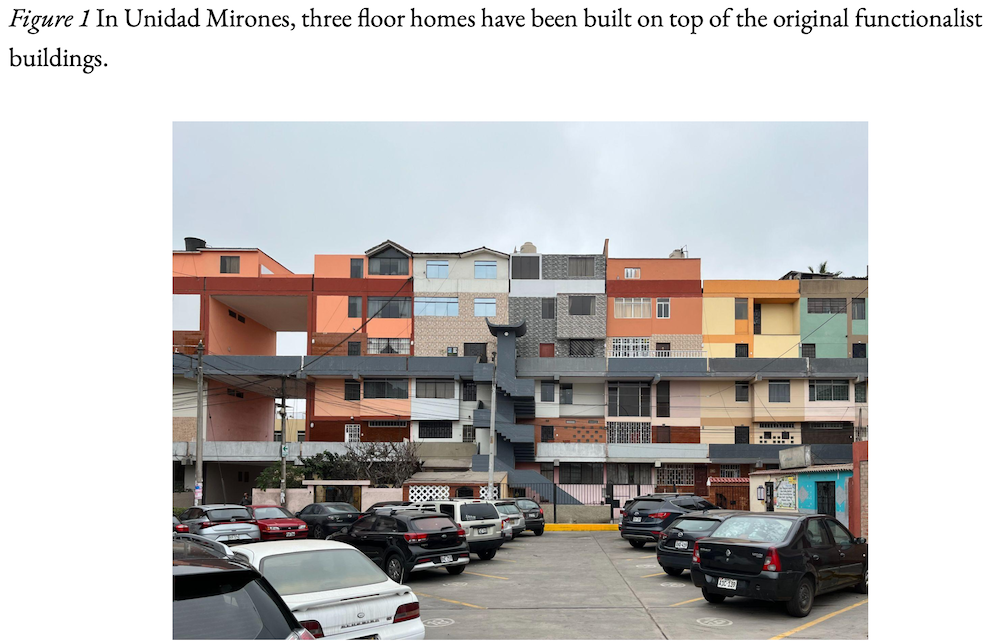

In Lima, I visited Unidad Mirones, a mid-century public housing project that has been deeply personalized by its inhabitants. Residents have painted their corresponding facades to their taste, balconies have been added and subtracted, and three-poor homes have been built on top of the original units (Figure 2). While the personalization of facades is often exalted for the diversity it engenders, it also becomes problematic when considering these housing projects as material heritage worthy of historical conservation. In Unidad San Felipe, the crown jewel of Peruvian social housing, the alteration of balconies has incited heated arguments among the residents that advocate for the preservation and those that favor adaptation.

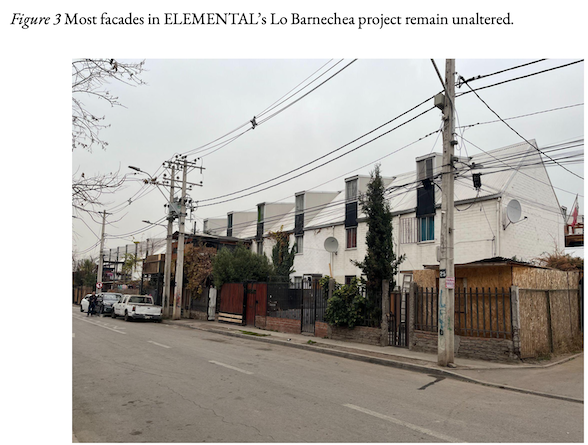

In Santiago I visited the ELEMENTAL offices, whose founder Alejandro Aravarena designed a system of half-built row houses that earned him the 2016 Pritzker Prize. There, I learned that this model had been replicated not too far away from the office, in the affluent neighborhood of Lo Barnechea. When I visited the Lo Barnechea project, I realized that the homes have been barely modified by its inhabitants, which is the premise of the model (Figure 3). There is a striking alienation between the community and its surroundings, and the residents shared with me their unease with the community’s

crippling drug-tracking problem. If a housing project enclaved in an upscale neighborhood, designed by a world-renowned social housing architect, was so ill-fated, how could successful social housing be intentionally designed?

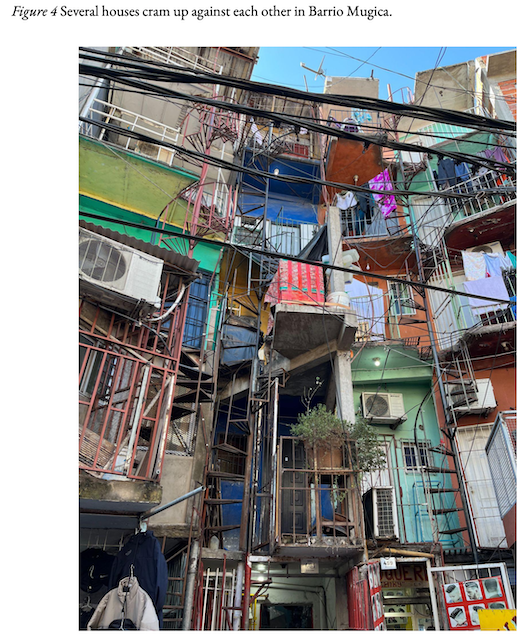

In Buenos Aires, I visited Barrio Mugica, the most infamous settlement in the Argentinian capital (Figure 4). Landlocked between the city’s port and a bridgeless canal that separates it from the affluent neighborhood of Recoleta, walking into Barrio Mugica is inconceivable for most porteños.

In recent years, several renewal programs have built social housing for the residents of Barrio Mugica. Yet urban renewal in Latin America does not always carry the negative connotations it does in the United States. For some inhabitants, the new developments are a literal breath of fresh air as they get ventilation and sunlight, clean water supply and sanitation, and larger apartments with open areas (Figure 5). For others, they signal a loss in diversity and the historical specificity that root the residents’ identities to the land.

Montevideo was different from the rest, considering that most affordable housing is not built by the government, but by a fascinating system of institutionalized cooperatives that promote self-building and common ownership.

Since the 1990s, most governments have abridged their building programs and privatized the construction of affordable housing. This shift has commoditized housing and alienated the historical relationship between state, housing, and society that shaped twentieth-century Latin American cities. Unlike the United States, the Latin American countries I visited recognize housing as a human right1. That is certainly not to say that housing is accessible to all, but that there is an expectation for it to be. Privatization of the affordable housing supply is an unequivocal violation of this right, and I fear for how the production and nourishment of social housing will look like in the future. While the role of the architect in this process remains unclear to me, my summer exploration of the relationship between historical and current modes of inhabitation in Latin America has inspired me to enlist in the crusade for dignified universal housing.

1 While the current 1980 Chilean Constitution overturned the right to housing established by the 1925 Constitution, most of the projects I visited were built before 1980. The new constitution, which was rejected half-way through the writing of this report, did acknowledge the right to affordable and dignified housing.

By Chucho Martinez ‘23, enrique.martinez@yale.edu